![[Translate to Englisch:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/d/6/csm_Website_Landing_Page_Top_c5e326c216.jpg)

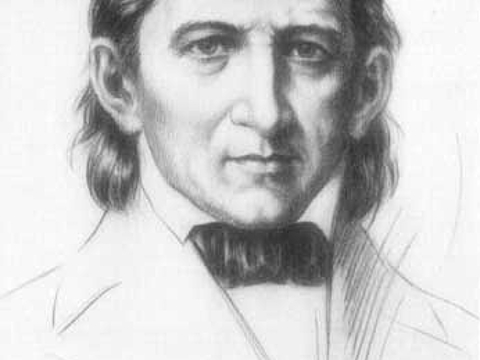

Friedrich Fröbel - the Inventor of Kindergarten

Prior to the 19th century, few people thought to educate children before the age of seven. So it was a big idea indeed when the German educator Friedrich Fröbel (1782-1852) opened the first kindergarten in 1837, grounded in “play and activity” and the nurturing of creativity through the systematic deployment of a sequence of “gifts” (coloured balls, geometrical building blocks, mosaic tiles, etc). Fröbel was using nature as the model of perfection to educate children. His goals were to teach children how to learn, observe, reason, express and create through play, employing philosophies of unity and interconnectedness. Kindergarten grew to become a familiar institution throughout the world by the end of the 19th century.

“The kindergarten that many of us grown-ups remember is one of songs, games, playing with blocks, finger painting and nature walks. But today, many kindergartens have become simply smaller first grades, teaching numbers and letters and giving tests and homework. In his book 'Inventing Kindergarten', Norman Brosterman makes a strong argument that the inspiration for much of modern art and architecture can be linked to the invention of the kindergarten - its playful rather than its academic incarnation - in the mid-19th century.

[…] Although the kindergarten quickly became widespread in America and Europe, Fröbel received little or no credit for his momentous invention. Born in Oberweissbach in central Germany, Fröbel was trained in science and became a teacher at a model school in Frankfurt in 1805. He studied with the Swiss educator Johann Pestalozzi - the first to translate Rousseau's radical educational philosophy into practice - and developed a distrust of formal education as he began to put faith in children's ability to learn through play, or activities that they initiated and directed themselves. He was unique at the time in believing that young children should receive some education before they entered school. He called his program 'kindergarten', or ‘children's garden’, a name he came up with during a walk in the woods, and opened his first one in 1837.

Fröbel created songs and games for mothers to use with their infants (‘This Little Piggy’ and 'Happy Birthday' apparently have a Fröbelian ancestry). He offered no formal instruction in morals and character, but thought that children naturally acquired such traits by caring for living things like the plants and animals that have become a fixture in most kindergarten classrooms. Perhaps Fröbel's most important contributions to early childhood education were what he called his 'gifts' (objects ranging from simple forms like spheres, cubes and cylinders to entire sets of wooden geometric blocks in different sizes and colors) and 'occupations' (the ways these materials could be manipulated by children). One 'gift', for instance, was a wooden pin that children could use to create patterns by punching small holes in sheets of paper, and Fröbel's kindergartners used sticks and dried peas much the way modern children use Tinker Toys. […] What Fröbel hoped to achieve with these tools - and with the kindergarten experience as a whole - was not the instruction of isolated facts and skills but 'the creation of a sensitive, inquisitive child with an uninhibited curiosity and genuine respect for nature, family and society.” (David Elkind, Play’s the Thing, New York Times, 7/09/1997, reviewing Norman Brosterman’s “Inventing Kindergarten”)

Fröbel's method inspired and informed the work of Maria Montessori, Rudolf Steiner, and others, who adopted his ideas and adapted his materials according to their own work. Prior to Friedrich Fröbel very young children were not educated. Fröbel was the first to recognize that significant brain development occurs between birth and age 3. His method combines an awareness of human physiology and the recognition that we, at our essence, are creative beings. Once early childhood education became widely adopted, it was the natural starting point for innovations that followed. Montessori and Steiner both acknowledged their debt to Fröbel, but the influence of the Kindergarten informs Reggio Emilia, Vygotsky and later approaches.